They’re Not Just Hacking Your Site. They’re Moving In.

On January 22, 2026, our database monitoring systems flagged something unusual across our customer base: administrator accounts that shouldn’t exist. Not just one or two stray accounts on a neglected site. We were looking at a coordinated campaign playing out across more than 15,000 websites.

What we found wasn’t a smash-and-grab. It was a move-in. Attackers weren’t just breaking into sites. They were setting up infrastructure to ensure they could come back, even after the initial breach was discovered and cleaned. The sophistication of the persistence techniques surprised us – and we’ve been doing this since 2007.

This is what we found, how we found it, and what we did about it automatically – before most site owners even knew they had a problem.

Note: We’ve also seen this same strategy with other plugins: wp-file-manager is very commonly used in this same manner.

The Vulnerability: Modular DS and CVE-2026-23550

Modular DS is a WordPress management plugin used on over 40,000 sites to handle backups, updates, and monitoring across multiple WordPress installations. In January 2026, PatchStack announced a critical privilege escalation vulnerability that was discovered in versions 2.5.1 and below, tracked as CVE-2026-23550 with a CVSS score of 10.0 — the maximum severity rating.

The flaw was rooted in a combination of design decisions that, when chained together, allowed an unauthenticated attacker to gain full administrator access. The plugin exposed internal routes, and those routes were supposed to be protected by authentication processes. But the authentication could be bypassed entirely by supplying two simple URL parameters – no secret key, no cryptographic signature, no IP validation. Just two predictable query string values.

Once past authentication, the attacker could hit a login endpoint that automatically authenticated them as an existing administrator on the site. The code would look up an admin user, generate valid session cookies, and redirect to the WordPress dashboard. Full admin access, zero credentials required.

A second exploit path, tracked as CVE-2026-23800, was discovered shortly after. This one allowed attackers to create new administrator accounts via the WordPress REST API, again without authentication, by exploiting the same bypass mechanism. The plugin’s code would set the current user’s authentication to that of an administrator, allowing execution of any REST route with full privileges.

The Modular DS team responded quickly (within 82 minutes of notification). Version 2.5.2 patched the first vulnerability, and version 2.6.0 addressed both. But by the time the patches landed, the attackers were already inside. This isn’t about that as a point of entry.

Hackers love persistence!

Phase One: The Invisible Administrators

The first thing attackers used was stolen login credentials. Then after gaining access they created new administrator accounts. No surprise there – that’s standard operating procedure. What wasn’t standard was how they hid them.

WordPress counts administrators by querying the wp_usermeta table for entries where the meta_key matches the active table prefix followed by “capabilities” and the value contains “administrator.” This is how the dashboard generates that familiar “Administrators (3)” count on the Users page. The attackers manipulated the database entries so that WordPress’s user list query wouldn’t return their accounts in the visible table – but the accounts still had full administrator privileges.

The result: a site owner logs into their dashboard, navigates to Users, and sees “Administrators (3)” in the count. But only two accounts are listed. Most people wouldn’t notice. Most people don’t cross-reference the count with the visible list. The attackers are counting on that.

These bogus accounts typically used long usernames with numbers and Gmail addresses — designed to look plausible enough to survive a casual glance at the database, but not recognizable to the site owner.

Our database monitoring caught this in real-time. Our system independently queries wp_users joined with wp_usermeta and counts administrators directly. When the count didn’t match what WordPress’s dashboard would display, or when new administrator accounts appeared that weren’t created through the standard WordPress registration flow, we flagged it immediately. Our automated response deleted the bogus accounts and reset all administrator passwords across affected sites.

But the hidden admin was only the first layer.

Phase Two: Maintaining Persistence In The Form of a Plugin

Here’s where it gets clever. The attackers knew that hidden admin accounts, once discovered, would be deleted. They needed a way back in that didn’t depend on having an active account on the site. Their solution: install a plugin with a known vulnerability and use that vulnerability as a re-entry point. Or, if the site already had the plugin, replace the files with the vulnerable version.

We observed two variations of this across our customer base:

On sites that already had Modular DS installed and updated to a patched version, the attackers replaced the current, patched files with files from the vulnerable version 2.5.1. The site owner had done everything right – updated promptly after the advisory – and the attackers undid it. Without most ever knowing.

On a small number of sites that never had Modular DS installed at all, the attackers installed it from scratch at the vulnerable version and activated it. We saw this a few times. (If you’ve ever used this plugin, you know they have a relatively detailed activation process) A fresh plugin that the site owner never chose, running a vulnerable version. Most website owners don’t closely monitor their list of installed plugins. The attackers are counting on that, too.

Now it gets really interesting. After installing the vulnerable, non-patched version, the hackers replaced the version and Stable Tag with the new, patched version and Stable Tag.

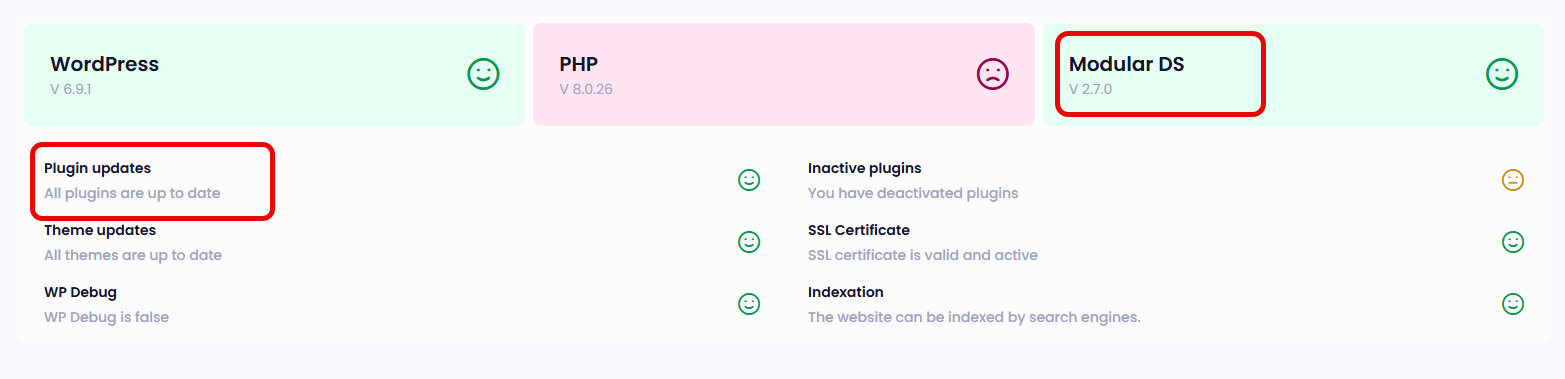

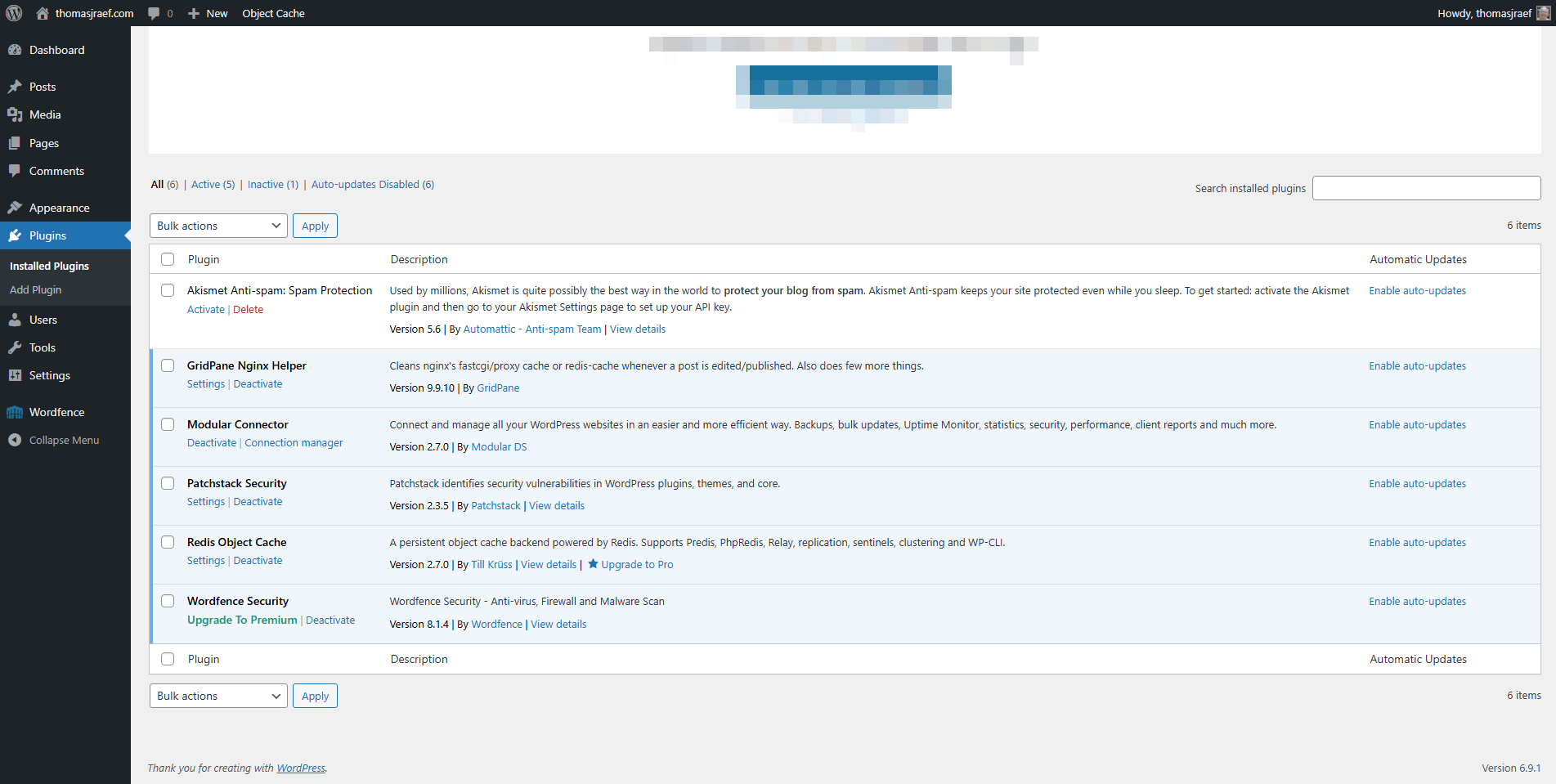

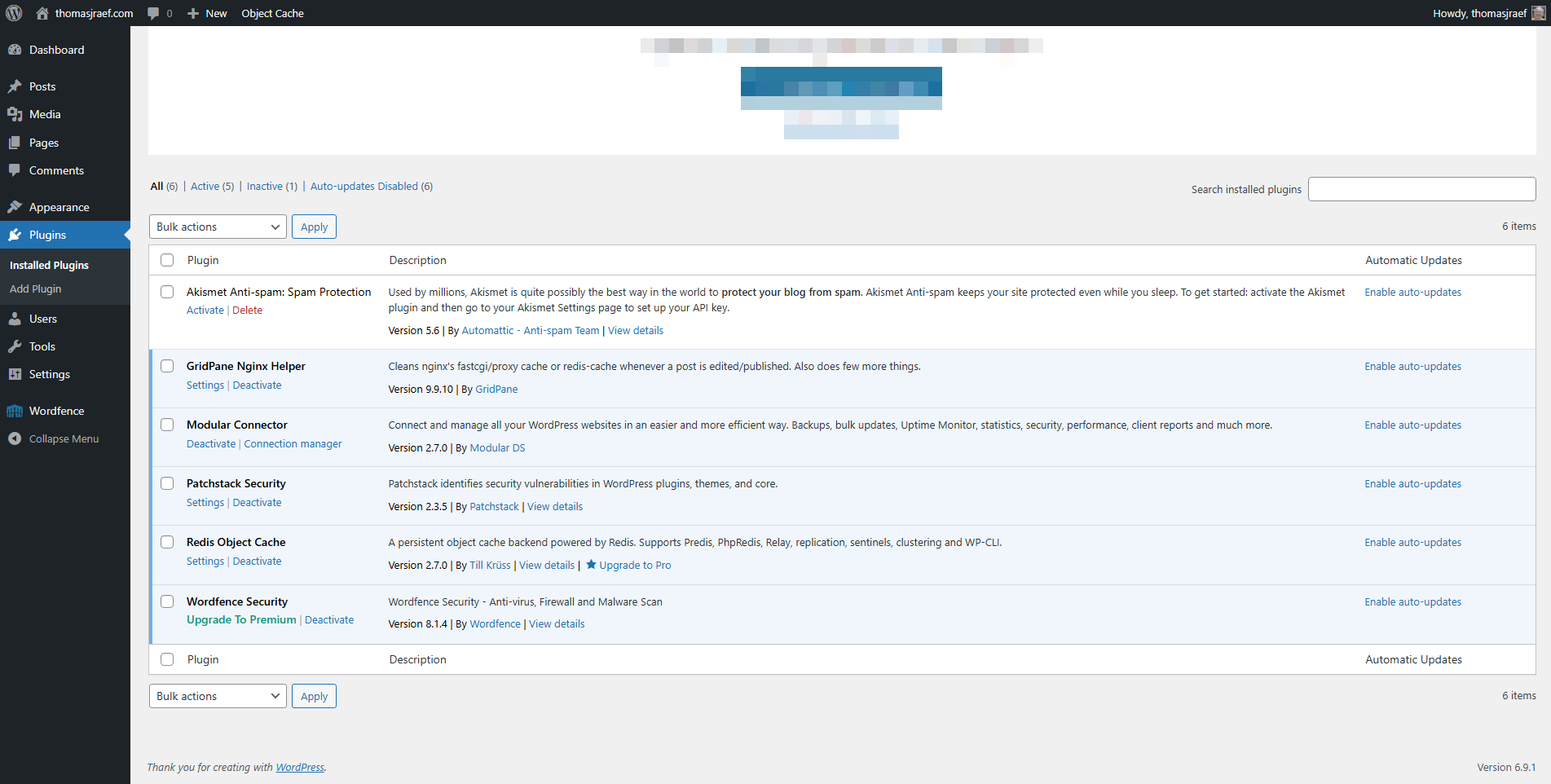

Here’s a screen shot from the modular-ds dashboard after the files had been replaced:

Think about what this means. Even if you discover the breach, delete the rogue admin accounts, and change all passwords, the attacker can walk right back in through the vulnerable plugin. And if you didn’t know the plugin was vulnerable – or didn’t even know it was installed – you’d never understand why your site keeps getting recompromised.

Phase Three: Version Spoofing — The Files Lie

Some of the attackers went a step further. They didn’t just install the vulnerable files – they changed the version numbers to make them look current.

WordPress determines a plugin’s version from two places: the Version header in the plugin’s main PHP file, and the Stable tag in readme.txt. These are what the dashboard displays and what WordPress uses to check for available updates. If these strings say the plugin is at a current version, WordPress won’t flag it.

We found sites where the actual plugin code was from version 2.5.1 — the vulnerable version — but the version headers had been edited to read 2.7.0:

In the readme.txt:

Stable tag: 2.7.0

In the plugin’s init.php:

* Version: 2.7.0

A site owner checking their plugins page would see “Modular DS 2.7.0” and assume they were running a safe, patched version. WordPress’s own update mechanism would agree – no updates available. Everything looks fine.

Everything is not fine. The actual PHP code handling requests, the code with the authentication bypass, is still the 2.5.1 codebase. The version string is just text in a comment block. It has no bearing on what the code actually does.

This is why version strings cannot be trusted for security verification. The only reliable way to confirm a plugin’s integrity is to compare actual file contents against known-good hashes from the official distribution. Our file integrity monitoring does exactly this. We don’t just ask the plugin what version it claims to be. We compare what’s on disk against what the WordPress.org repository says those files should contain for the claimed version. When the hashes don’t match, we know the files have been tampered with – regardless of what the version header says. We started doing this when we realized often times hackers hide backdoors, real PHP files, in the multi-level folders of a plugin. This scenario really paid off!

Proof of Concept: We Verified It

We didn’t just theorize about this, or witness this in real-time. We verified it.

On a test site running the vulnerable version of Modular DS (2.5.1), we compared the actual file contents on disk against the official 2.7.0 release from the WordPress.org repository. What we found confirmed exactly what we’d been seeing in the wild.

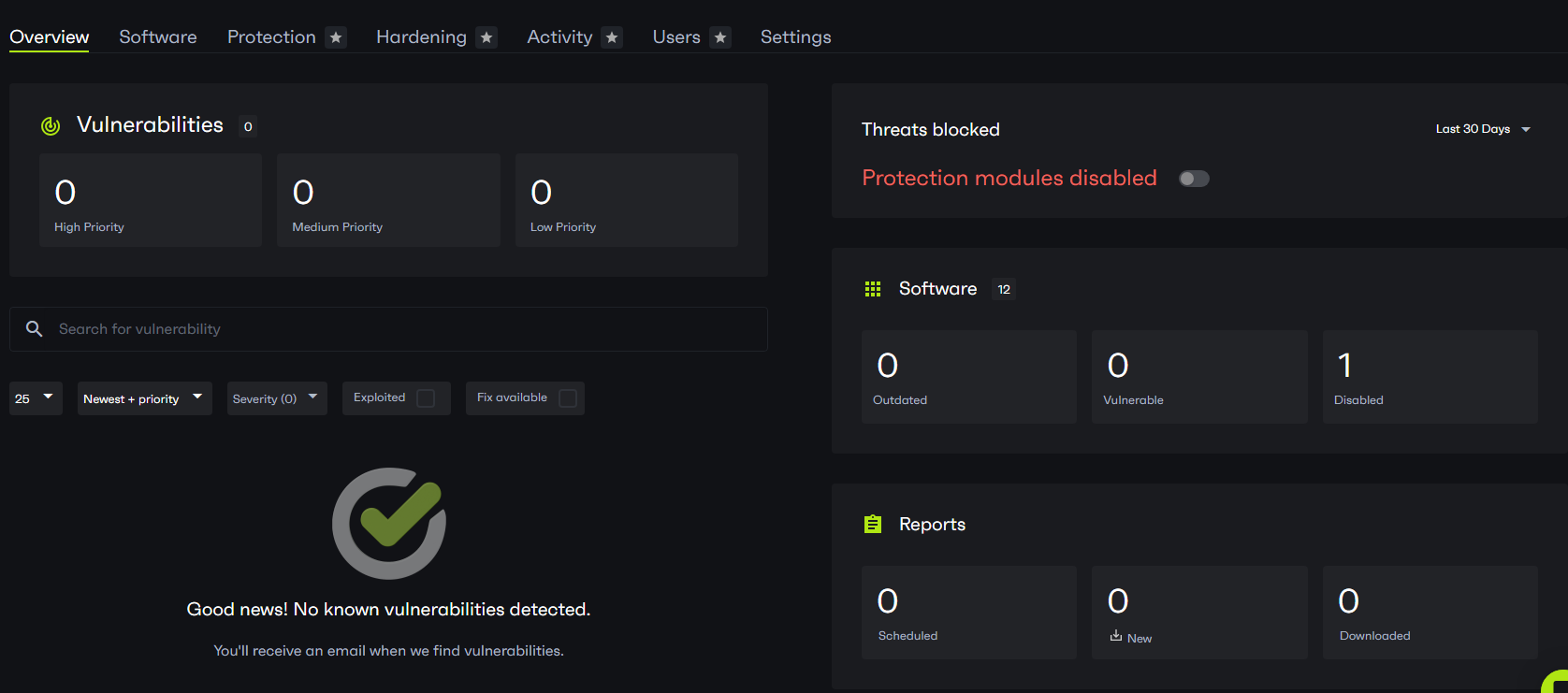

Here’s a screen capture from the Patchstack dashboard after spoofing the Version and Stable Tag numbers.

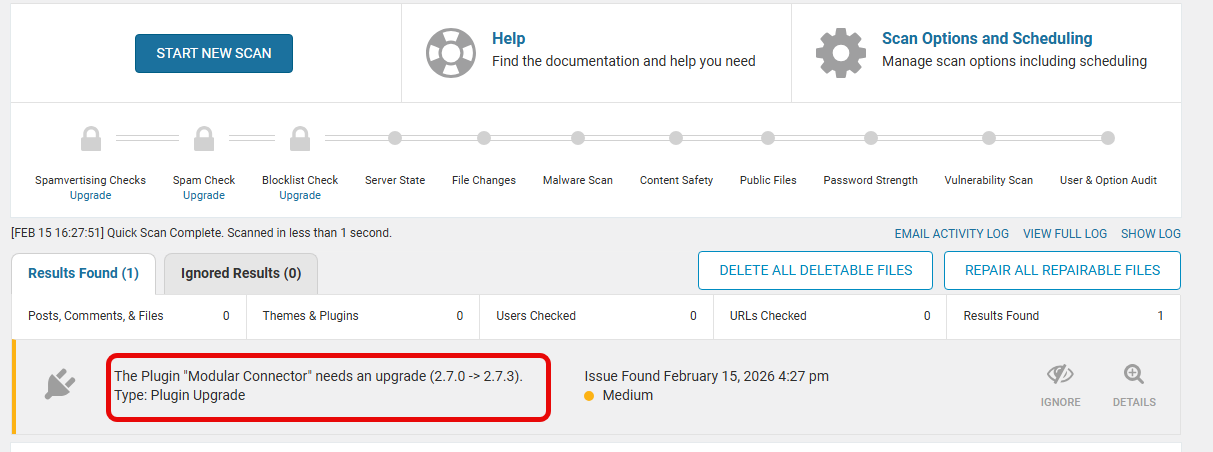

Here’s what Wordfence shows after spoofing the Version and Stable Tag numbers. (This screen shot was later and by that time ModularDS had release 2.7.3 update)

What WordPress Sees

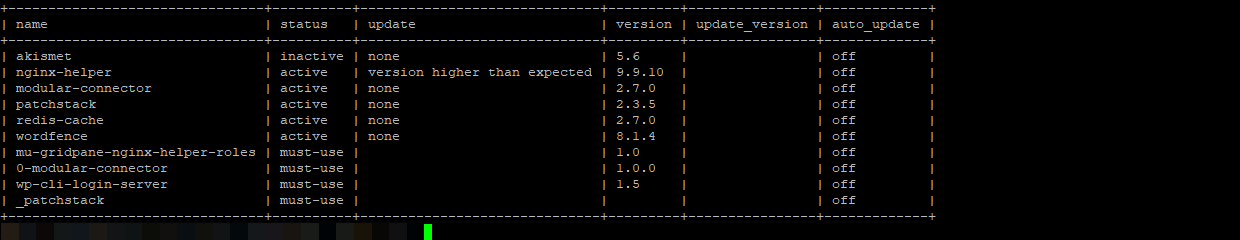

WordPress reports version 2.7.0. WP-CLI reports version 2.7.0. No updates available. The dashboard shows a healthy, patched plugin.

What the Hashes Reveal

SHA-256 hashes don’t lie. When we compared the installed HttpUtils.php — the critical file containing the authentication logic — against the official 2.7.0 release, the hashes didn’t match:

Installed (reporting 2.7.0, but actually 2.5.1 code):

f6582017080c2f753e25bec6873e546f3b4516065411de5c8dda7a9306d6d790

Official 2.7.0 release:

0d35e56679a5874e40b2949927c88ba1149f9ff41c3852cb12deae0647f29a6a

The file hash on the installed plugin does not match the official 2.7.0 release, despite the plugin reporting 2.7.0.

We generated SHA-256 manifests of every file in the plugin directory and compared them against the official distribution. Out of 3,542 files, over 100 PHP files had different hashes — spanning controllers, middleware, routing, authentication, database models, service providers, and vendor libraries. The entire security-critical core of the plugin had been replaced while the version string stayed the same.

What’s Missing from the Installed Code

The real 2.7.0 release introduced extensive security hardening — a complete rewrite of the authentication bypass that the attackers exploit. Their team went above and beyond to make sure this never happens again. The diff between the vulnerable and patched versions of HttpUtils.php alone is 547 lines. Here’s what the patched release added that the installed code lacks entirely:

- Entry point validation — the patched version verifies requests originate from

wp-load.php, not arbitrary URLs - HTTP method restriction — only GET requests are accepted; the vulnerable version didn’t check

- Type allowlisting — only three specific values are accepted; the vulnerable version accepted anything

- Authentication requirements — the patched version requires either a signed parameter or an authentication header; the vulnerable version required neither

- UUID validation on request IDs — the patched version validates request identifiers as proper UUIDs

- Parameter whitelisting — the patched version rejects any unexpected query parameters; the vulnerable version ignored them

- Exclusive parameter sourcing — values can come from query string OR header, but not both, preventing injection attacks

Every one of these protections is absent from the installed codebase. The site is running the original authentication bypass wide open — and WordPress reports everything is fine.

Spot the difference? There isn’t one. Both dashboards show Modular Connector at version 2.7.0 with no updates available. The image on the left is running the real, patched 2.7.0. The image on the right has had over 100 PHP files replaced with vulnerable code. WordPress can’t tell them apart.

The Blind Spot: Why Most Security Scanner Can’t Detect This

Here’s the part that should concern every WordPress site owner and every hosting provider: most malware scanners on the market will not detect this attack.

Originally, I wrote that none of the malware scanners could detect this. I have since been informed by reliable sources that Wordfence does in fact have the option of detecting differences in files on a website for plugins, themes and core with originals. I apologize for originally posting wrong information. Sucuri apparently verifies core files; wp-admin and wp-includes, but not wp-content folder/sub-folders.

The reason is simple: there is no malware. Every single file the attacker drops on the server is a legitimate, unmodified plugin file — distributed by a real developer through the official WordPress.org repository. There’s no obfuscated code. No webshells. No base64-encoded payloads. No suspicious function calls. No eval() or preg_replace with the /e modifier. No encoded strings being decoded at runtime. Nothing that any malware signature, heuristic, or pattern-matching engine would flag.

The files are clean. They’re just old.

The “malware” is the version. The weapon is a legitimate file. And that’s a class of threat that falls completely outside the detection model of every major WordPress security plugin.

Every Security Tool Shares the Same Blind Spot

It goes deeper than malware scanning. Every security plugin in the WordPress ecosystem determines plugin versions the same way WordPress itself does: by reading the Version: header in the plugin’s main PHP file. That’s it. There is no checksum verification. There is no comparison against the official release. There is no integrity check of any kind.

WordPress reads the header, says 2.7.0. WP-CLI reads the header, says 2.7.0. Wordfence reads the header, says 2.7.0, no known vulnerabilities for this version. Patchstack reads the header, says 2.7.0, you’re patched. The WordPress.org update API compares the header against the latest release and says no update available.

Every single tool in the ecosystem is asking the plugin “what version are you?” and trusting the answer.

Nobody is checking the actual code.

It’s like airport security asking a passenger “are you a threat?” and letting them through when they say no.

This isn’t a bug in any one product. It’s a systemic architectural flaw in how the entire WordPress security ecosystem handles plugin integrity. Version-header trust is baked into WordPress core, and every tool built on top of it inherits the same blind spot. Until a tool compares actual file contents against known-good distributions — byte for byte, hash for hash — this attack is invisible.

File Integrity Monitoring Is a Different Approach

Our file integrity monitoring doesn’t ask the plugin what version it claims to be. It hashes the actual files on disk and compares them against the official release for the claimed version. When the hashes don’t match — when a plugin says it’s 2.7.0 but the files are 2.5.1 — we know. Not because the files are “malicious” in any traditional sense, but because they’re not what they claim to be. Like stated earlier, we added this checking of files back months ago when we started seeing more backdoors buried deep in plugin folders.

That distinction — between scanning for malware and verifying integrity — is the difference between catching this attack and missing it entirely.

The Entry Point: Stolen Authentication Cookies

How did the attackers get initial access to install these backdoors? While the Modular DS vulnerability itself could be the initial exploit for the campaign, it didn’t appear it was. What we observed on approximately 15% of affected sites was particularly telling.

These sites showed a pattern: a legitimate administrator would log in normally. Then, typically within about 10 hours, the same account would authenticate again – but from a completely different IP address, and very different user agent (we know, user agent is easily spoofed) one belonging to a known compromised host. And there was no visit to wp-login.php. The session went straight to plugin-install.php because with the authentication cookies, they’re already authenticated.

That’s a stolen authentication cookie.

When you log into WordPress, your browser stores a session cookie. If someone else obtains that cookie, they can use it to access your site as you, without ever needing your password and without going through the login page. The cookie is the credential.

These cookies are most commonly stolen through malware on the administrator’s own computer – information-stealing trojans that harvest browser cookies and send them back to command-and-control servers. The turnaround was fast. WordPress authentication cookies are valid for 48 hours by default, or two weeks if the user checks “Remember Me.” The attackers were using the stolen cookies within hours of the legitimate login, maximizing the window before the cookie expired.

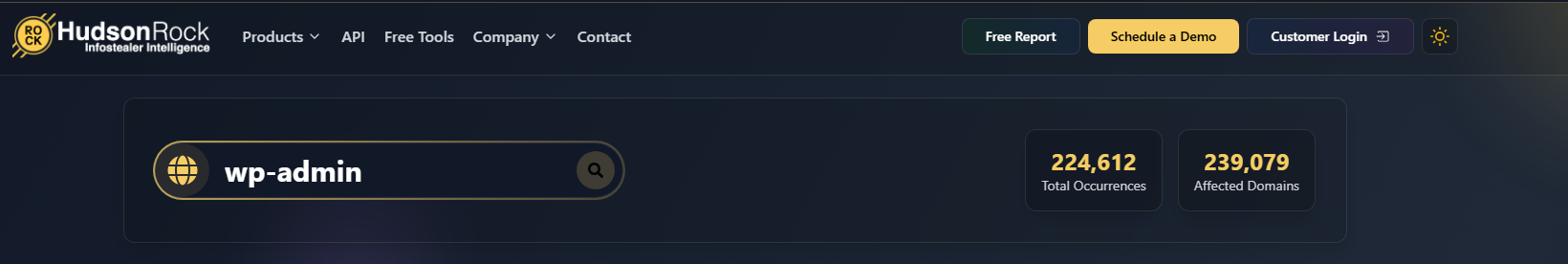

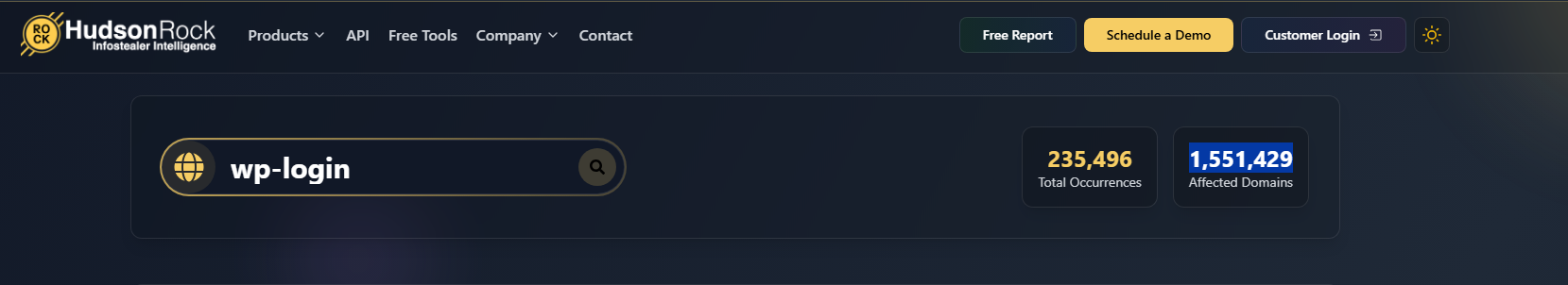

According to Alon Gal, Co-Founder & CTO at Hudson Rock (they track stolen credentials):

Hudson Rock tracks hundreds of thousands of exposed WordPress admin panels (including wp-admin access via stolen credentials + cookies) from global infostealer infections, turning everyday sites into high-value targets.

The behavior signature was unmistakable: legitimate login from the admin’s normal location, followed by a session from a suspicious IP that skipped the login page entirely and went directly to installing plugins. This would totally bypass 2FA. Our systems flagged these sessions based on the geographic and behavioral anomalies (different location and/or browser/computer within 24 hours).

We did not see any indication that modular-connector plugin was used as the initial point of entry. They were used as a later stage point of re-entry.

The “Can You See Me Now?” Problem

As if all this wasn’t bad enough. We would see files pop-up on our radar (real-time file monitoring) and then disappear. The hackers were creating self-deleting backdoors. We could see the traffic in our log analysis, response 200 for a given file, with traffic from various IP addresses, then the traffic would stop and the file would disappear.

What we found was various backdoors that were self-deleting after carrying out their instructions.

// Deletes itself 60 seconds after creation

if (time() - filemtime(__FILE__) > 60) {

@unlink(__FILE__);

die();

}

The Checklist Problem

When a vulnerability like this makes the news, the security community responds with advisories. And those advisories almost always end the same way: with a checklist.

Check for bogus admin accounts. Scan the wp_users table. Look for injected JavaScript. Review admin logs. Reset all passwords. Inspect traffic for C2 connections.

Let’s be honest about what this advice actually means for the average site owner.

“Check for bogus admin accounts.” They’ll log into their dashboard, look at the Users page, see the same accounts they’ve always seen, and move on. They won’t notice that the administrator count is one higher than the number of visible users. They won’t think to query the database directly. The attackers designed it that way.

“Scan the wp_users table.” With what? Most site owners don’t know how to navigate the database. Many don’t know what phpMyAdmin is. The ones who do likely don’t know what a suspicious wp_usermeta entry looks like versus a legitimate one.

“Look for injected JavaScript.” Where? In which files? What does injected JavaScript look like versus the legitimate JavaScript that every plugin and theme includes? Are they supposed to read through every .js file on their server?

“Review admin logs.” WordPress doesn’t ship with admin activity logging. Unless they’ve installed a logging plugin and configured it, there are no logs to review.

“Inspect traffic for C2 connections.” This requires server-level access, knowledge of network analysis tools, and the ability to distinguish normal outbound traffic from command-and-control communication. Even if IP addresses found in the research are provided, there are always more. This isn’t advice for site owners. This is advice for a security operations center.

The gap between what security advisories tell people to do and what people can actually do is enormous. And attackers are operating in that gap.

What Automated Security Monitoring Actually Looks Like

Here’s what happened on the sites we monitor when this campaign hit.

Our database monitoring detected the hidden administrator accounts in real-time. Our system doesn’t rely on the WordPress dashboard to count administrators. It queries the database independently, cross-referencing wp_users with wp_usermeta and comparing the results against known legitimate accounts. When new administrator accounts appeared that weren’t created through standard channels, they were flagged immediately. The bogus accounts were automatically deleted. All administrator passwords were reset.

Our file integrity monitoring detected the vulnerable plugin installation. When new plugin files appeared on disk, our audit monitoring daemon detected the file additions in real-time. The system identified the files as belonging to a vulnerable version of Modular DS and blocked the plugin from being accessible. On sites where the attacker replaced a patched version with vulnerable files, the integrity check caught the mismatch between claimed version and actual file contents – and blocked access.

Our monitoring identified and removed injected JavaScript. When the attackers injected malicious JavaScript into existing theme and plugin files, our file integrity monitoring saw those modifications the moment they happened. When malicious javascript was injected into core files, our file integrity monitoring detected that and replaced the infected core files with originals. Automatically. The injected code was identified using our malware detection engine – built on a database of over 300,000 malware samples collected over 17 years – and removed automatically.

Our systems identified admin sessions originating from compromised hosts. By monitoring authentication patterns, we detected sessions that bypassed the login page and originated from known-bad IP addresses. These sessions were flagged as credential theft, and affected accounts were secured.

None of this required the site owner to do anything. No checklist. No database query. No JavaScript audit. No log review. The detection and response happened automatically, and the site owner received a report explaining exactly what was found, how the attackers got in, and what was done about it.

Why Root Cause Analysis Matters

Most security services, if they detect an infection at all, without manual verification, will clean it up and move on. They’ll remove the malware, delete the rogue admin, and call it done.

Two weeks later, the site is reinfected. Because nobody explained how the attacker got in. Nobody found the vulnerable plugin they planted as a backdoor. Nobody caught the version-spoofed files masquerading as a patched release.

Root cause analysis is what separates incident response from incident repetition. When we respond to a compromised site, we don’t just clean what we find. We trace the full attack chain: initial access vector, persistence mechanisms, lateral actions, and exfiltration. We tell you that the attacker gained access via a stolen authentication cookie, created a hidden admin account with a spoofed database entry, installed a vulnerable plugin with forged version headers, and injected JavaScript into three specific files.

That level of detail is why our reinfection rate is 0.047%. When you understand exactly how an attacker got in and exactly what they did to ensure they could come back, you can close every door. Not just the one you happened to find first.

A Note for Hosting Providers

This campaign affected sites across every major hosting platform. The attackers weren’t targeting specific hosts — they were targeting the obtained login process and the plugin vulnerability wherever it existed.

If you’re a hosting provider, your customers are looking to you for security. When one of their sites gets compromised, your support team takes the call. When they get reinfected after a cleanup, they blame the hosting. When they find out their “secure” hosting didn’t detect an invisible admin account or a backdoored plugin, they leave.

We’ve been protecting WordPress sites since 2007. We monitor over 2 million websites globally. Our malware detection engine has been trained on 300,000+ samples. These aren’t just signatures that can be easily bypassed. We created our own LLM that has learned from these samples. We provide the kind of automated, real-time detection and response that turns a compromise into a non-event for your customers — and turns a support headache into a competitive advantage for you.

If you’re interested in learning how we can protect your customers, we’d like to talk. Because the attackers aren’t slowing down. And a checklist isn’t going to stop them.

Indicators of Compromise

For security professionals and hosting operations teams, the following indicators may be present on affected sites:

- Discrepancy between WordPress administrator count and visible users in the dashboard

- Administrator accounts in wp_usermeta with non-standard capability key prefixes

- Modular DS / Modular Connector plugin present at version 2.5.1 or below, or with version headers claiming 2.6.1+ but file hashes matching the 2.5.1 distribution

- Modular DS plugin ZIP files in wp-content/uploads/

- Admin sessions that access plugin-install.php without a preceding wp-login.php visit

- Administrator authentication from IP addresses associated with unknown hosts, particularly within 10 hours of a legitimate admin login

- New administrator accounts with long usernames and random numbers at Gmail addresses

- Requests to /api/modular-connector/login/ with origin=mo&type= parameters (primary exploit path, CVE-2026-23550 — this is the re-entry vector through the vulnerable plugin)

- REST API requests to /?rest_route=/wp/v2/users with origin=mo&type= parameters (admin account creation, CVE-2026-23800)

We Watch Your Website has been providing WordPress security monitoring and malware removal since 2007. To learn more about our automated detection and response capabilities, contact: traef@wewatchyourwebsite.com.